Tahltan Nation

Home / Who We Are / Tahltan Nation

Tahltan History

We have lived in and occupied Tahltan Territory since time immemorial. Our Nation comprises two primary Tahltan clans, Crow and Wolf, which were each divided into matrilineal sub-clans.

Around 1875, after smallpox wiped out most of our people, the leaders of the sub-clans agreed to amalgamate under a single leader. This represented the Nation’s move away from a hereditary system towards a system that is reflected in today’s Tahltan Nation governance.

Our identity, and the essence of who we are as a distinct society, are integrally tied to the land and the wealth of the resources therein. Our connection to the land is paramount. We claim sovereign rights to our Territory as articulated in the 1910 Declaration of the Tahltan Tribe.

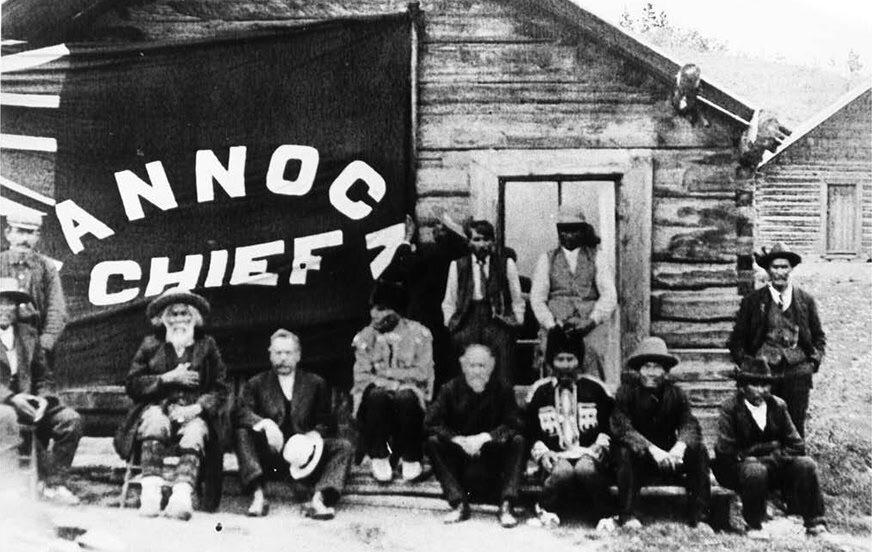

In 1910, Tahltan Chief Nanok, along with 80 other Tahltan leaders, signed the Tahltan Declaration. The document asserted our traditional continued sovereignty over Tahltan land. It declared that any land interests concerning Tahltan Traditional Territory must be settled directly with the Tahltan people.

As we continue to advance our culture and Nation, we rely on the same territory and resources that sustained our ancestors. Many Tahltan people continue to practice a subsistence economy, which includes fishing, hunting and gathering.

About the Tahltan Nation

The Tahltan Central Government is the administrative body responsible for managing the Tahltan Nation’s Rights and Title. The Iskut Band serves as the administrative body for the community of Iskut, while the Tahltan Band serves as the administrative body for the communities of Dease Lake and Telegraph Creek.

The Tahltan population is approximately 4,000 members. Approximately 800 members live in one of three communities in Tahltan Territory – Tatl’ah (Dease Lake), Łuwechōn (Iskut), and Tlēgōhīn (Telegraph Creek). Around 3,200 Tahltans reside outside the Territory.

Tahltan Culture

Tahltan culture is intricately woven into all aspects of language, art, governance, law and everyday life.

Our stories and legends preserve our history and guide our way of relating to all living things. As an example, our stories provide inspiration to talented Tahltan artists, who enshrine our stories into beautiful moccasins, drums, blankets and other valuables. These are just some of the ways in which Tahltan culture is preserved and shared with the world.

Our culture is organized through a matrilinear clan system. This means that crests and inheritance are passed down through the mother. Since time immemorial, this system has provided the basis of Tahltan law and governance. Despite the imposition of a settler society form of government (through the Indian Act), the matrilineal system remains the foundational governing structure of the Tahltan people.

The Tahltan Nation is divided into two clans, the Crow (or Tsesk’iya) and the Wolf (or Ch’ioyone). Each clan is further divided into several family groups. Legends about the Crow and Raven continue to guide the Tahltan people about the best way of living, for example, by the principles of determination, generosity and resourcefulness among others.

Raven Creation Story

As told by Rosie Dennis

This is a Raven story.

How silly could he be? He could make himself into anything. Raven saw that one guy, a wife and daughter had daylight, sun and the moon. Only their place, a brush house, had light. And this whole earth was just pitch dark, yet people lived on it, and Raven thinks to himself, “How could I get the lights away from those people – how could I make myself so that girl could swallow me? Then she’ll bear me, and I’ll cry for daylight first, then I’ll cry for the sun, and then I’ll cry for the moon.”

So, he made himself a little dust – that’s how crow does that, he made himself dust and this young girl eats it. He puts himself on that girl’s food so she could swallow him and have a baby. The girl spots it and tells her mother to look at the dust on her food.

They claimed that’s the story. Those people were so neat and clean that nothing would come near them because they were the only ones that had light. And the crow thinks, “Oh I don’t know what to do now – what could I make myself so that girl wouldn’t see me, so she’ll swallow me? She has a wood cup.” And the crow thinks, “Oh, if I put myself around the rim of that cup, make myself a small little dust, I bet that way she’ll swallow me.” So, he did! Sure enough the girl didn’t see it and she swallowed that little dust.

In a few months, it’s showing that she’s pregnant – and her mother and Dad ask how did she get pregnant, how could we find out? They couldn’t find out, nobody came around, it was just them. Finally, she’s in labour; here it was the boy that was that crow! The way grandma and the old timers tell us, they say it’s a true story.

So, the mother of the girl tells her husband, put up your camp outside my daughter’s, she’s in labour. So, her dad put up a little brush house. He moved out of there, that’s our Indian way when a woman is going to have a baby. When a woman is in labour, the man has to move out till the woman has the baby – so that’s what they did.

Here it was that boy! That baby grew up fast, they figure he started creeping around in about a week. The grandfather and the grandmother loved that kid so much it isn’t funny! And when he figured that he was big enough to carry the daylight, sun and the moon, he cried for daylight.

But first he cried to his grandpa. He points to that daylight; he can’t talk but he points to that daylight. So, his grandpa asks his wife, “Shall we give to him? He wouldn’t spoil it.” The grandmother said, “He might cry himself to death, give it to him.” So, the grandfather brings it down, and hands it to him. He played with it so long; he cried for the sun. Then he pointed to the sun, and he wanted that too.

They both said the same thing, he might cry himself to death – we better give it to him, so they gave him that sun. When he bounced the daylight and sun together, the grandpa and the grandma just hollered! Then he started to cry for the moon. They tried to give him something else, but he wouldn’t take it, he wouldn’t quit crying so they figured that again he might cry himself to death – so they gave him that moonlight.

Now he had all three of them – he practised when they weren’t looking at him. He asked himself, “I wonder if I can fly out through that smoke hole – they have a big brush house! I wonder if I can lift it and fly out through that smoke hole?” No, he thought to himself. So, he waits for another day, I don’t know how long after, then he starts same thing again – daylight first, then sun, and moonlight. They give it all to him, and he plays with it and finally he tests himself again to see if he can fly with it.

All of a sudden, he could hold all three of them – that daylight, sun, and moon. “Caw, caw, caw,” and he flies out through that smoke hole.

That’s the time all the animals holler, the first thing that hollers is the marten sitting on a tree, and the grizzly bear was at the foot of that tree, under that tree. He’s got no moccasins on. The marten hollers, “Daylight break, daylight break.” The goat runs to the bluff, the beaver dives in the water, the bear runs in a den. When the daylight broke, all the animals, wherever they settled, that’s where they are today. The grizzly bear sat under that tree where the marten was. He said, “Daylight break, daylight break, run away daylight break.” Grizzly bear put his moccasins on the wrong way, that’s why grizzly bear’s back foot is wrong you see – he was so excited he put his moccasins on the wrong way. When they heard daylight break, all the animals got so scared they ran to where they live. It’s that way right up to today – how does that grab you?

Tahltan Territory

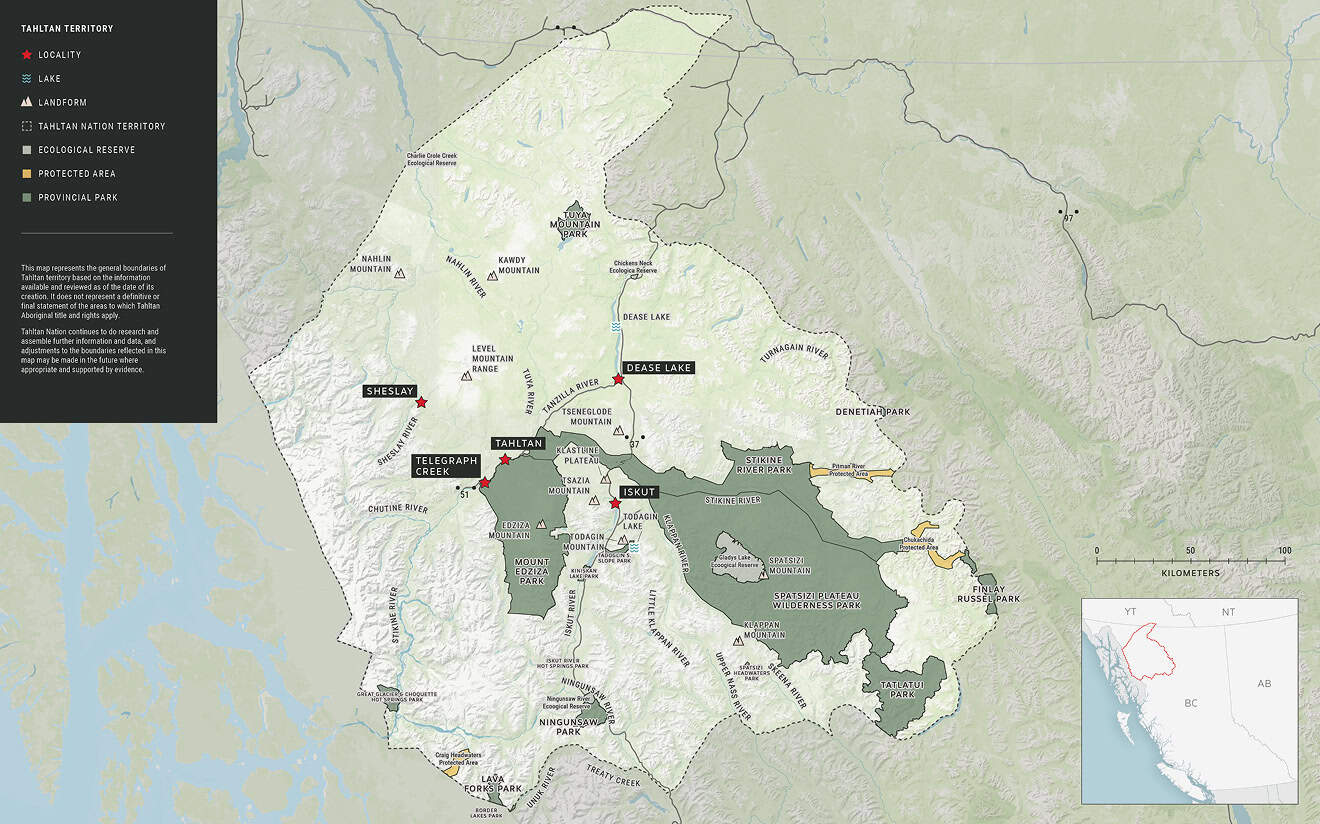

Tahltan Territory is 95,933 km2 or the equivalent of 11% of British Columbia.

If the Tahltan Nation were its own country, we would be bigger than Portugal and slightly smaller than South Korea. The territory is rich in natural resources and continues to garner international attention for its mineral potential and abundant wildlife.

- Approximately 70% of BC’s resource rich Golden Triangle.

- Two of BC’s 10 operating metal mines or their shared footprint.

- Approximately 50% of BC’s exploration activities by expenditure, 13% of Canada’s, and 2.5% of the world.

- $330 Million total amount of mineral exploration expenditures in Tahltan Territory, including KSM and Brucejack (actual $ 329,743,000).

- $1.15 Billion total mining production value (actual $1,151,421,358 – Red Chris and Brucejack).

History of Mining

Mining is part of Tahltan culture. For thousands of years, Tahltans prospected and mined obsidian. In the late 1800’s, Tahltans supported miners during the gold rush. With 70% of B.C.’s resource rich Golden Triangle located in Tahltan Territory, Tahltans are a sophisticated mining Nation, now with generations of modern industry experience.